The two-pot retirement system, which is set to be implemented on 1 September 2024, has been designed to improve retirement outcomes for South Africans by ensuring that the majority of their future retirement fund contributions remain invested for their retirement, while allowing some access before retirement in case of emergencies. If used as intended, the new rules can assist retirement fund members in achieving higher and more sustainable incomes in retirement. However, a few missteps, some of which may seem harmless, have the potential to offset a lot of the new rules’ good intentions. Shaun Duddy discusses how the new rules aim to improve retirement outcomes and the risks that need to be avoided to achieve this.

The two-pot retirement system is set to be implemented on 1 September 2024. While we believe that the new rules are a positive step for South Africa’s retirement system, whether they actually assist retirement fund members in achieving a better retirement will still come down to individuals making good decisions and avoiding the risks that exist within the framework of the new rules. At a high level, this involves understanding:

- Whether the new rules improve or worsen the preservation rules of your retirement fund

- The risk of withdrawing from – and worse, depleting – your savings component before retirement

- The risk of treating and investing your savings component like a shorter-term investment

- The fact that the new rules alone do not ensure an appropriate and sustainable income in retirement

But first, to aid these considerations, let’s refresh the two-pot basics.

Summarising the basics

From 1 September 2024, all new retirement fund contributions will be split into two components (i.e. the two “pots”):

- Two-thirds of every contribution you make will be allocated to a retirement component. The assets in this component cannot be accessed before retirement and, at retirement, must be used to purchase a retirement income product, such as a living annuity or guaranteed life annuity. This component ensures that the majority of your future retirement fund contributions remain invested until retirement to provide you with an income.

- One-third of every contribution you make will be allocated to a savings component. As contributions to a retirement fund, the assets in this component should also, ideally, remain invested until retirement to provide you with income. However, this component also provides the option to make one withdrawal (of R2 000 or more) per tax year before retirement if you need to. This access is designed to help you in case of emergencies when, without such access, the alternative would likely lead to worse financial outcomes (e.g. taking on high interest rate debt). You also have the option to access these assets as a cash lump sum at retirement. As is the case today, any amount taken from your retirement fund as cash is subject to tax. This is discussed in a bit more detail further on.

Your existing retirement fund assets will be allocated to a vested component, and the current (i.e. pre-two-pot) rules will continue to apply. Ten percent of the assets you hold on 31 August, up to a maximum of R30 000, will be allocated to your savings component on 1 September to provide an opening balance on day one. This is referred to as the “seeding” of the savings component and will only happen this one time, at the start of the new system. The balance of your existing assets will remain in your vested component and nothing will change for these assets.

“Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should” is arguably the best saying to apply to your savings component under the two-pot retirement system.

As an example, if a retirement fund member has R200 000 in their retirement account on 31 August and is contributing R6 000 per month, the following will happen on 1 September:

- 10% of their existing assets, up to a maximum of R30 000, will be seeded to their savings component. In this case, R20 000 will be seeded (i.e. 10% of R200 000, which is less than R30 000).

- Their account will have a savings component of R20 000 and a vested component of R180 000 (i.e. the remaining balance) on day one.

From September onwards, the said retirement fund member’s monthly contributions will be allocated as follows: R2 000 (i.e. one-third of R6 000) to the savings component, and R4 000 (i.e. two-thirds of R6 000) to the retirement component, which begin to build up both of these components.

All of the above will apply to each of your retirement accounts. For example, if you have a pension fund account through your employer and an Allan Gray Retirement Annuity Fund (AGRA) account in your personal capacity, the changes will apply to each. The same is true if you have three AGRA accounts: We will apply the changes to each of them individually, including the seeding of each account’s savings component. The only exception is if you have a provident fund account that you have had since before 1 March 2021, and you were 55 or older on 1 March 2021. By default, the new rules will not be applied to that account (but will be applied to any other account you may have).

The “Two-pot retirement system” page on our website provides comprehensive information about the changes, while Lydia Fourie’s piece covers the most frequently asked questions to assist you in filling in any gaps. However, understanding the “mechanics” of the changes is only step one. Below, we begin to unpack the real implications and risks of the new rules and what missteps to avoid for better retirement outcomes.

Will the two-pot retirement system improve or worsen the preservation rules of your retirement fund?

Although the two-pot retirement system’s primary objective is to improve preservation, the extent to which the new rules improve or worsen preservation rules depends on the type of retirement fund in which you are investing.

Let’s start with pension and provident funds, including preservation funds. If you are investing for retirement in one of these funds, the new rules will assist with improved preservation going forward. This is because, under the current rules, you are able to take up to 100% of your assets as cash from your pension or provident fund each time you change employers or leave an employer, or as a once-off withdrawal from your preservation fund. In all of these cases, your withdrawals will be net of the applicable taxes. In the worst case, if you withdraw everything and do not invest it elsewhere, you effectively have to start all over again with fewer years to rebuild this investment before you retire.

In contrast, under the new rules, the assets in your savings component will be accessible (once per tax year, in the case of an emergency, which might be when you change employers or leave your employer) and the assets in your vested component will still be accessible (when you change employers or leave your employer), but the assets in your retirement component cannot be accessed. Automatically preserving the assets in your retirement component assists in ensuring that a minimum amount of assets remain invested until and for retirement.

In the case of new retirement fund members starting to invest on or after 1 September 2024, a minimum of two-thirds of their retirement fund assets will make it to retirement, which is a substantial improvement compared to the current rules. Over time, allowing access to the savings component should also reduce (and ultimately remove) the often-counterproductive incentive to leave one’s job in order to access retirement fund assets, as well as the instinct to take all of them when doing so.

… any withdrawal from your savings component will be taxed at your marginal tax rate …

However, on the other side of the coin, we have retirement annuity funds (RAs). Here, the new rules actually run the risk of worsening preservation. Under the current rules, you cannot access any of your retirement fund assets before age 55, even if you change jobs or lose your job. In other words, RAs have always had 100% preservation. This will change with the introduction of the savings component under the new rules: A portion of your retirement fund assets will now be accessible. To the extent that this access is used as intended, to assist you in case of emergencies, it is a positive. However, the risk is that this access introduces a new temptation to access your retirement fund assets, potentially reducing preservation and ultimately resulting in a lower and less sustainable income in retirement.

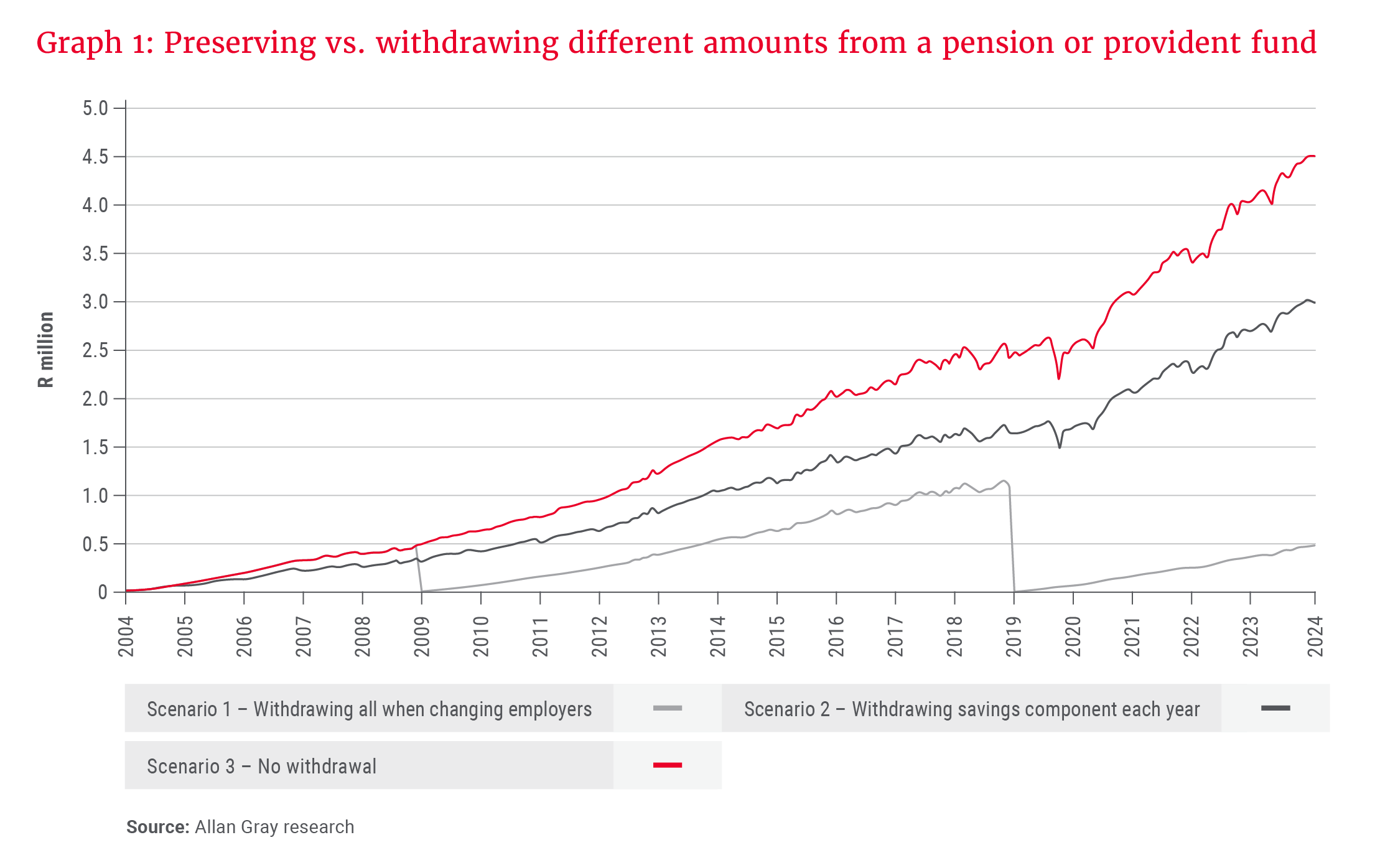

To illustrate these scenarios, Graph 1 looks at different outcomes for a pension or provident fund member contributing R6 000 per month over the last 20 years and investing in the Allan Gray Balanced Fund. In Scenario 1 (the light grey line), they take all of their retirement fund assets when they change employers at the end of year 5, and again at the end of year 15, which is allowable under the current rules. Scenario 2 (the dark grey line) assumes that the new rules apply: One-third of each contribution (i.e. R2 000) is allocated to a savings component, two thirds of each contribution (i.e. R4 000) is allocated to a retirement component, and only the full savings component is taken each and every year. Lastly, Scenario 3 (the red line) assumes that nothing is taken when changing employers. Relative to Scenario 1, after 20 years, the member would have 6.3 times more in Scenario 2 and 9.5 times more in Scenario 3. This illustrates the power of preservation and how the new rules can improve preservation in pension and provident funds.

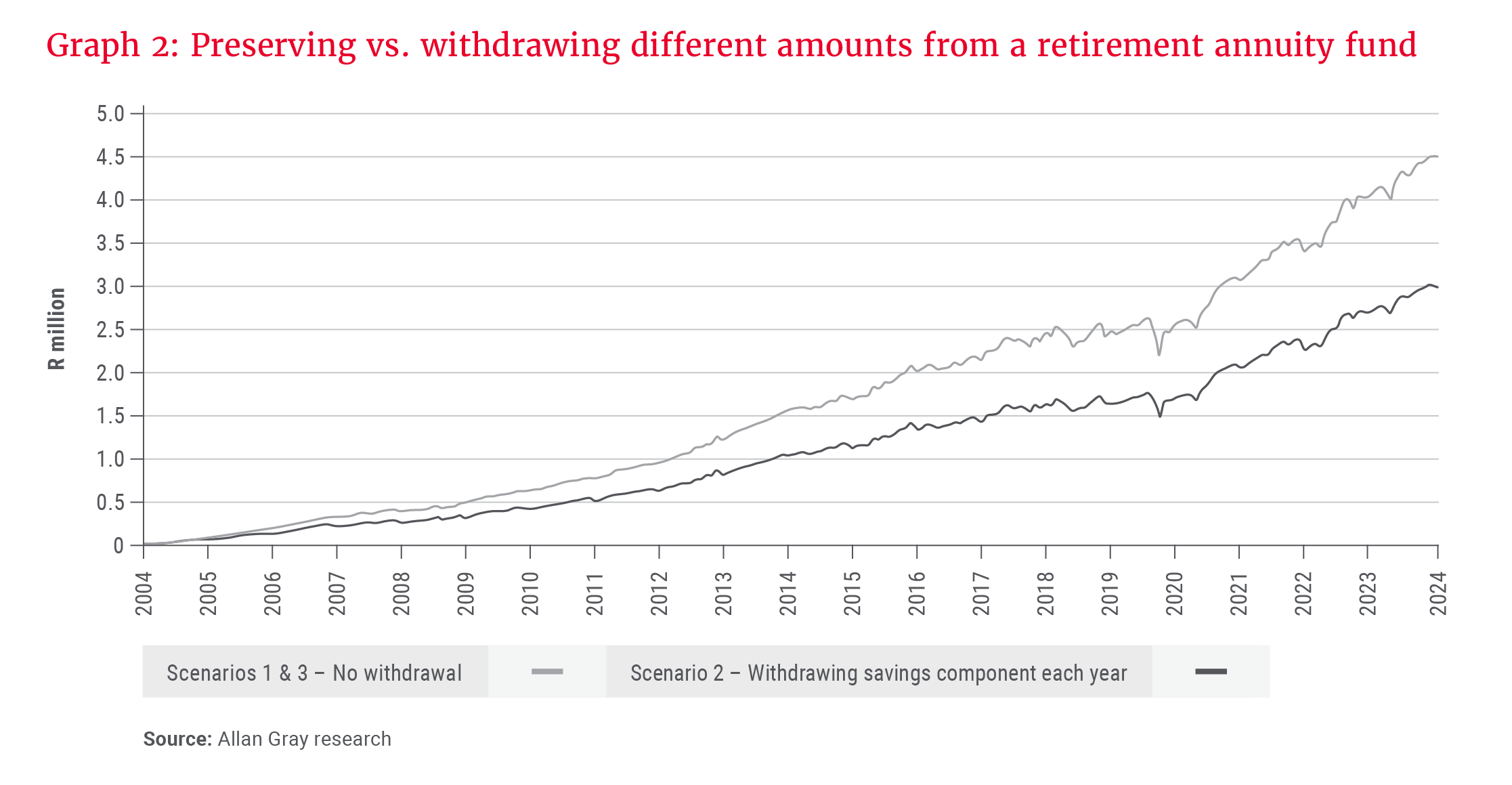

Graph 2 shows the same scenarios for a member of an RA. However, for Scenario 1 (the light grey line), no assets are accessible under the current rules when changing employers, therefore Scenarios 1 and 3 (as described in Graph 1) are equal. This graph again shows the importance of preservation. However, it also shows that the ability to “only” access the savings component under the new rules, as represented in Scenario 2 (the dark grey line), is actually a negative relative to the current rules for this type of retirement fund.

The risk of withdrawing from – and worse, depleting – your savings component before retirement

“Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should” is arguably the best saying to apply to your savings component under the two-pot retirement system. As mentioned, you will be able to make one withdrawal (of R2 000 or more) per tax year before retirement, but it is highly recommended that you do not, except when you find yourself in a real financial emergency and not withdrawing would lead to a worse financial outcome. Comparing Scenarios 2 and 3 in Graphs 1 and 2 gives a good illustration of why these withdrawals are not recommended, but the significance of this risk warrants further discussion.

The most important (and arguably most obvious) points to make are:

a) Any assets that are withdrawn and not replaced before retirement will reduce your income in retirement.

b) The longer you wait to replace the assets, the more you will have to invest to make up for lost time and investment returns.

New retirement fund members starting to invest on or after 1 September also need to keep in mind that if they deplete their savings component before retirement, they will not only have one-third less assets to provide an income in retirement, but also no assets that can be taken as a cash lump sum at retirement to cover bigger or once-off expenses, e.g. settling the remainder of their bond. It is important to remember that if you elect not to withdraw, your contributions will continue to accumulate and grow, and will be available to withdraw at a later stage, if need be.

Ultimately, the goal should be to keep as much as possible of your savings component invested until retirement.

You also need to keep in mind that any withdrawal from your savings component will be taxed at your marginal tax rate, which is above your effective tax rate (i.e. the tax rate applied to your salary) and can further be reduced if you have any outstanding taxes owed to the South African Revenue Service (SARS). These taxes are also higher than those applied at retirement if you decide to take your savings component assets, or a portion thereof, as a cash lump sum at that point. This is another compelling reason not to dip in.

Ultimately, the goal should be to keep as much as possible of your savings component invested until retirement. You lose nothing by not withdrawing every year, because all of your savings component assets remain available for withdrawal in future years, and you benefit materially from avoiding the associated risks.

The risk of treating and investing your savings component like a shorter-term investment

Even if you don’t withdraw from your savings component assets, you can still end up with a lot less income in retirement than you could have otherwise as a result of treating your savings component like a shorter-term investment and therefore investing it too conservatively.

You may be thinking: “I don’t plan to withdraw my savings component, but just in case I do find myself in an emergency situation, I am going to invest it in something lower-risk and safe.” While this may seem reasonable and reasonably harmless, it can have a material impact on the overall growth of your retirement fund assets, and your ultimate income in retirement. A far better option for emergencies is to build up an appropriately invested emergency fund, as Tebogo Marite discusses in her piece.

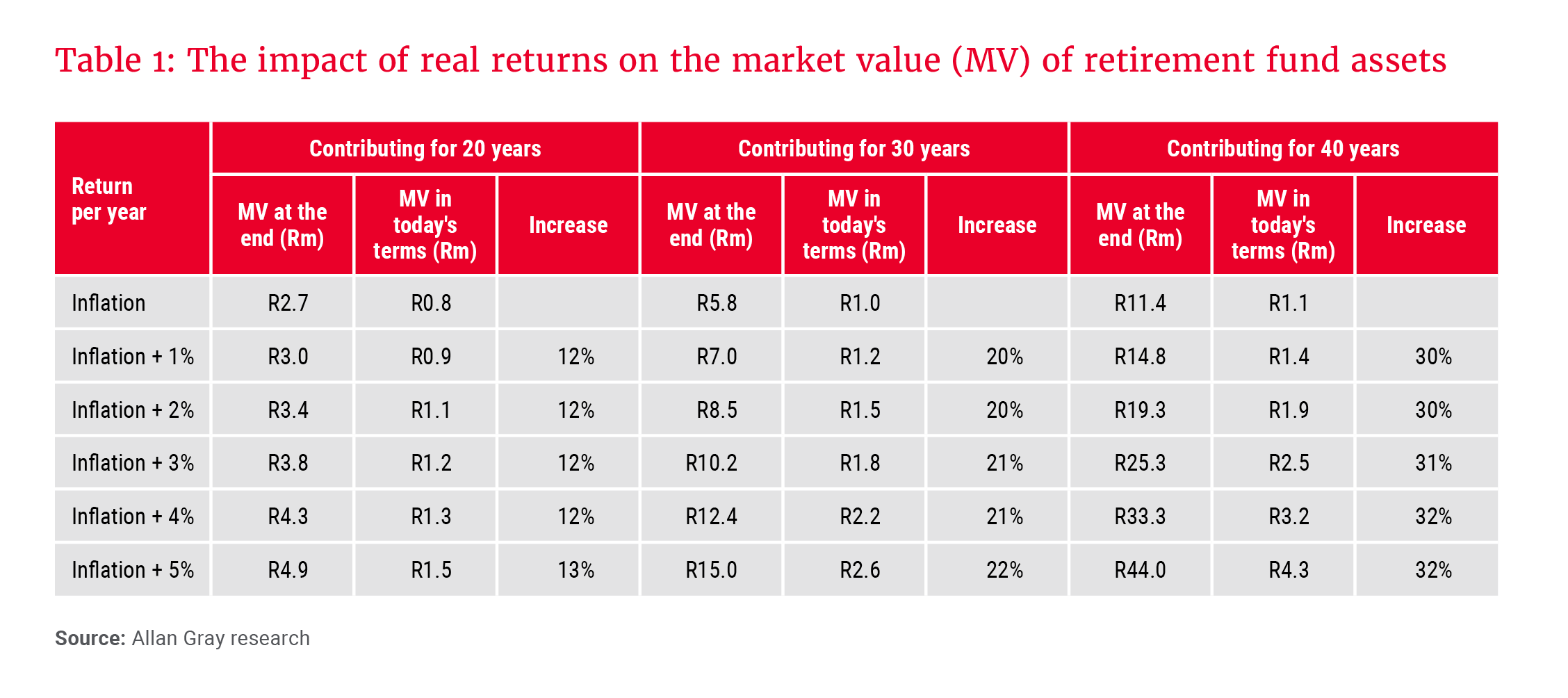

To truly grow your retirement fund assets, you need investment returns that are higher than inflation – i.e. real returns. Table 1 shows how much each additional percent of real returns can add to your assets at retirement, and therefore your income in retirement. The table assumes contributions of R6 000 per month, over different periods of time, experiencing different levels of return above inflation. Inflation is assumed at 6% per year and the investment returns are assumed to be consistent each year.

Table 1 shows the material impact on the market value at retirement for each additional percent of real returns: from a 12% increase for each additional percent over 20 years, up to a 32% increase for each additional percent over 40 years. For example, if a retirement fund member contributed R6 000 per month for 40 years (e.g. from age 25 to retirement at age 65), each additional per cent of real returns would increase their assets at retirement by 30% or more. In total, if the member was able to achieve investment returns of inflation + 5% per year instead of inflationary returns, they would have 3.8 times more at retirement, which is a massive difference. The reverse, however, is also true: Each percent of real returns that you do not achieve (or give up) can materially decrease your assets at retirement.

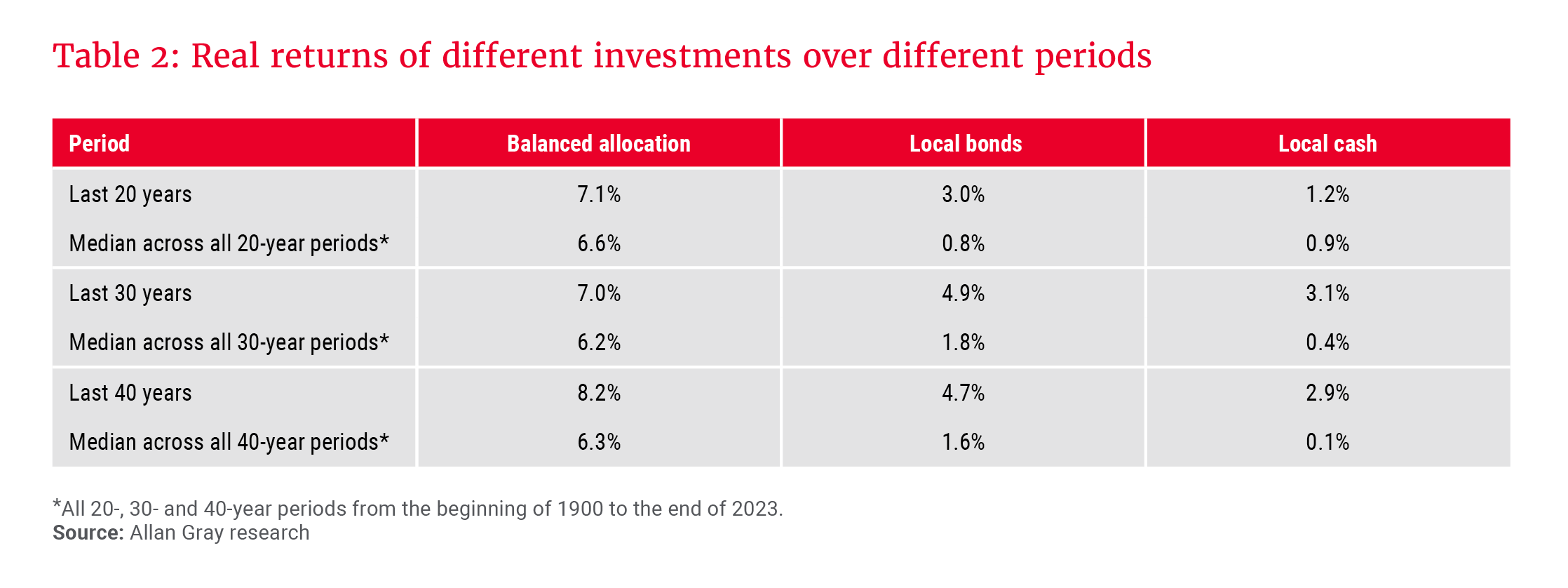

With that in mind, Table 2 compares the historic real returns of lower-risk investments, specifically local cash and local bonds, with investments in a higher-risk balanced allocation that is more typically appropriate for longer-term investments, like investing for retirement. The balanced allocation consists of 65% equities (39% local plus 26% offshore), 25% bonds (15% local plus 10% offshore) and 10% cash (6% local plus 4% offshore), and is 40% offshore in total. The return data used is a combination of the DMS Global Returns Data (1900 - 2012) and Morningstar data (from 2013 onwards) and includes all years from the beginning of 1900 to the end of 2023. What is clear from Table 2 is that investing your savings component like a shorter-term investment, in lower-risk assets, can cost you valuable real returns.

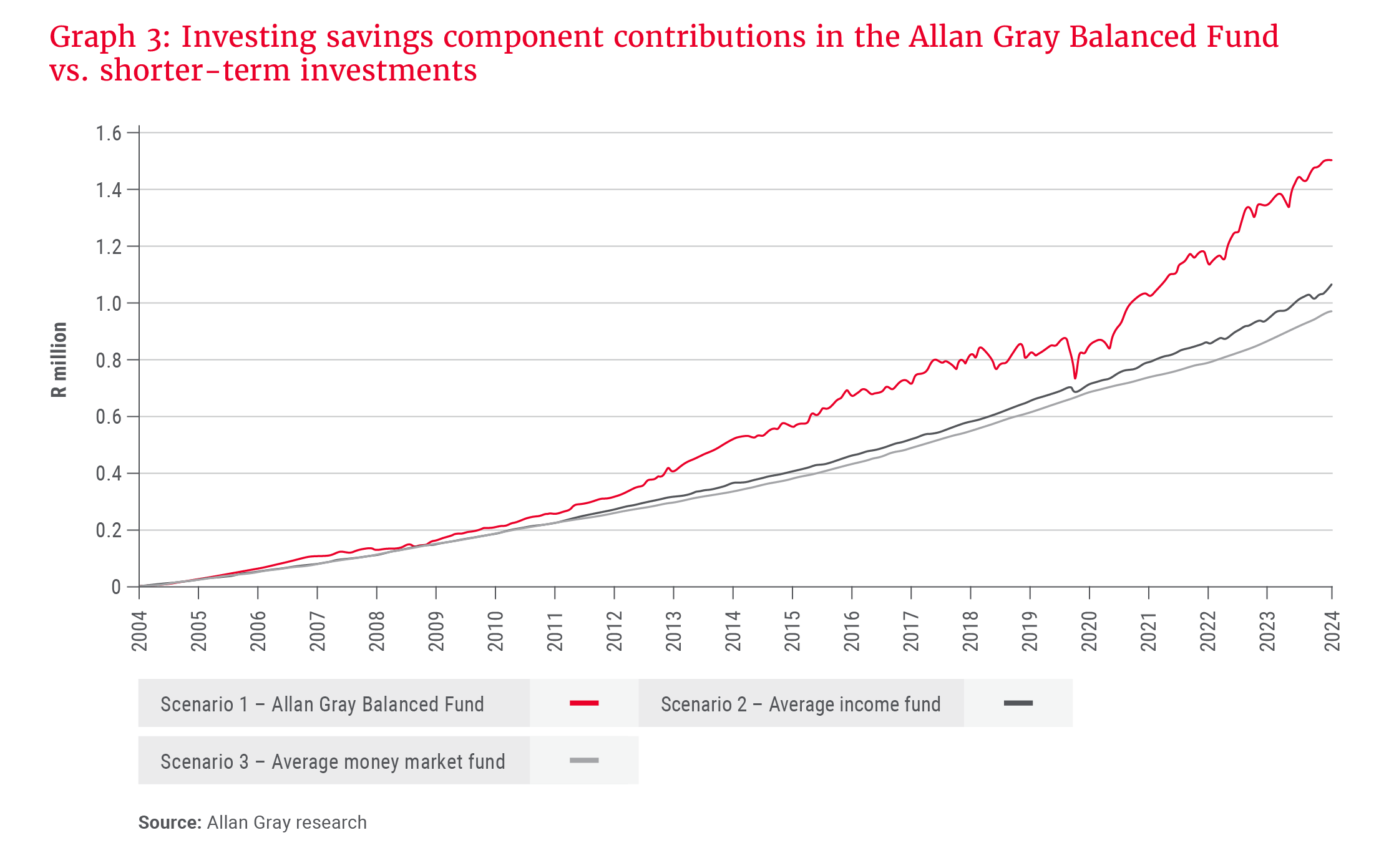

While the combination of Tables 1 and 2 clearly highlights the risk of investing your savings component like a shorter-term investment, it is also useful to show a scenario example. Graph 3 uses our retirement fund member from earlier, contributing R6 000 per month over the last 20 years. In Scenario 1, they invest the full contribution in the Allan Gray Balanced Fund (AGBF), in Scenario 2, they invest R4 000 in the AGBF and R2 000 in the average income fund, and in Scenario 3, they invest R4 000 in the AGBF and R2 000 in the average money market fund. After 20 years, and assuming no withdrawals, the member would have R1.5m in their savings component in Scenario 1 (the red line). In comparison, they would have 29.8% less in their average income fund in Scenario 2 (the dark grey line), and 35.6% less in their average money market fund in Scenario 3 (the light grey line). These are material differences, which, in turn, would translate into 9.9% and 11.9% reductions in their overall retirement fund assets. This again illustrates the importance of investing for real returns. Ideally, all of your retirement fund assets should make it to retirement, making all components long-term investments, which should be invested accordingly.

The two-pot retirement system alone does not ensure an appropriate and sustainable income in retirement

As illustrated across the previous sections, while the two-pot retirement system will assist with better preservation in a lot of cases, it is still up to you to avoid the withdrawal temptation and invest appropriately for real returns. In addition, this all still needs to be combined with regular investments, at appropriate levels, over a long period of time in the build-up to your retirement. The new rules are a very positive step for the South African retirement system, but in reality, it is ultimately the combination of these behaviours, and not the new rules alone, that will lead to better retirement outcomes.

For more on the two-pot retirement system, listen to Richard Carter and Shaun Duddy in conversation on The Allan Gray Podcast.